Independencia en las Américas, Parte 1

Independence Day in the Americas, Part 1

En honor del Mes de la Herencia Latinoamericana y los Días de Independencia de varios países hispanos, inclusive México, haremos una serie limitada sobre la independencia latinoamericana.

Aquí en los Estados Unidos, es muy conocido el día feriado el Cinco de Mayo. El día se ha vuelto famoso en este país como un día para celebrar la herencia mexicana, y en ello se puede encontrar festejos desde los más sencillos hasta los más íntimos. Muchas personas no mexicanas asumen, lógicamente, que el Cinco de Mayo conmemora la independencia mexicana. Pero están equivocados: el Día de Independencia mexicana se celebra el dieciséis de septiembre, recordando el famoso Grito de Dolores que ocurrió esa fecha en 1810, a unas 200 millas de la Ciudad de México.

Retrocedamos un poco. Por casi 300 años, desde 1521, España había administrado el territorio que hoy en día conocemos como México como su colonia más premiada. Se llamaba Nueva España y su ciudad administrativa, o capital, fue México, así nombrada por la tribu de los Mexicas, quienes habían sido la fuerza más potente en el Imperio Azteca y cuya capital, en su turno, había sido Tenochtitlan. Cuando Hernán Cortés y su bando llegaron allí en 1519, se estima que hubiera sido la ciudad tercera más grande en el mundo en ese entonces. Cuando Tenochtitlan fue destruida en el enfrentamiento entre español e indígena, los españoles construyeron a México sobre las ruinas.

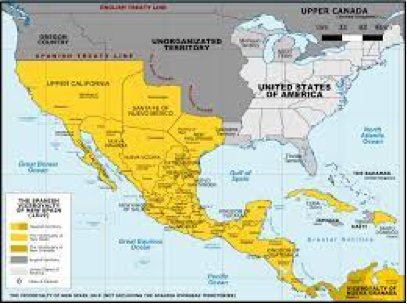

Los españoles ampliaron rápido su territorio. A saber que hubo plata en las desiertas de lo que hoy en día es Zacatecas, se emprendió una gran migración—muchas veces esforzada—de personas hacia el norte para hacer el trabajo arduo de las minas. La plata fue transportada primero a México, para cobrarle el quinto real (un impuesto de 20% del valor de la plata) y luego a la ciudad porteña de Veracruz, desde donde se zarpaba para Europa. Se estima que entre Zacatecas y Potosí, Bolivia, un 80% de la plata en el mundo fue minada en aquellos siglos.

Los españoles impusieron un sistema rígido de jerarquía en sus nuevas colonias, las cuales eventualmente compondrían una vasta área en el continente americano. Las personas nacidas en la misma España, denominadas peninsulares, encabezaban a todo. Justo debajo de estos eran los criollos, de “pura” sangre española pero nacidos en América. Debajo de ambas clases residían los indígenas, quienes por lo general fueron permitidos a vivir separados y seguir hablando su propio idioma, pero tampoco tenían muchos derechos o estatus en esta nueva sociedad.

Una cosa que los españoles no les permitían a los indígenas fue mantener su religión indígena. Los españoles de aquella época eran católicos romanos fervientes, y para ellos no era sólo una oportunidad, sino una obligación, a difundir la fe cristiana a sus nuevos súbditos. Hubo resistencia al principio, pero los españoles fueron persistentes en esta área, y además fueron ingeniosos. Por ejemplo, los españoles solían instalar sus iglesias en sitios que ya les eran sagrados para los indígenas, así conectándolas con las creencias indígenas. Un día, según la leyenda, un pobre indígena llamado Juan Diego vio a la Virgen María, quien impuso su imagen en el ayate que éste usaba. Con el tiempo, las personas con descendencia indígena llegarían a ser unas de las más fieles y fervientes católicas en Nueva España.

La colonia creció en importancia y prestigio para España a través de las décadas y después, los siglos. Con el tiempo, se podía notar debilidades fuertes en su sistema de jerarquía, la más obvia siendo que muchos niños nacieron de padres mezclados, es decir, por ejemplo, de un padre criollo y una madre indígena. Tales niños fueron denominados mestizos y aunque fueron negados acceso a los altos puestos de poder, tampoco fueron tan subyugados como los indígenas “puros”. Es fácil imaginarse que a través de las generaciones, estos mestizos componían más y más de la población de Nueva España.

Otra falla del sistema es que después de un principio, naturalmente, habían mucho más criollos en Nueva España que peninsulares, pero estos últimos seguían poseyendo más autoridad. Esta división crecía a través de los años, eventualmente causando muchos rencores entre estos dos grupos poderosos.

Cada década, una proporción más pequeña de peninsulares reinaba sobre una población más grande de criollos, indígenas, y, sobre todo, mestizos. Mientras Nueva España se acercaba a su cuarto siglo de existencia, el sistema estaba por reventarse. Una sola chispa bastaría para encenderlo todo.

Mark Plum es un escritor contribuyente del Index quien escribirá artículos sobre la cultura latina en el área de West Liberty. Plum dice que está abierto a casi cualquier idea en cuanto a sus historias; se puede ponerse en contacto con él marcándole al 319-471-0768 o escribiéndole a mplum@wl.k12.ia.us.

ENGLISH VERSION

In honor of Latin American Heritage Month and the celebration of Independence Day in several Spanish speaking countries, including Mexico, we will be doing a limited series on Latin American independence.

Here in the United States, the Cinco de Mayo holiday is well known. The day has become famous in this country as a day to celebrate Mexican heritage, and in it you can find celebrations from the simplest to the most intimate. Many non-Mexicans logically assume that Cinco de Mayo commemorates Mexican independence. But they are wrong: Mexican Independence Day is celebrated on September 16, recalling the famous Grito de Dolores from Miguel Hidalgo that occurred on that date in 1810, about 200 miles from Mexico City.

Let's back up a bit. For almost 300 years, since 1521, Spain had administered the territory that today we know as Mexico as its most prized possession. It was called New Spain and its administrative city, or capital, was Mexico, named after the tribe of the Mexicas, who had been the most powerful force in the Aztec Empire and whose capital, in turn, had been Tenochtitlan. When Hernán Cortés and his band arrived there in 1519, it is estimated that it would have been the third largest city in the world at the time. When Tenochtitlan was destroyed in the confrontation between the Spanish and the Aztecs, the Spanish built Mexico City on the ruins.

The Spanish rapidly expanded their territory. When they found out that there was silver in the deserts of what is now Zacatecas, a great migration was undertaken — often forced — of people to the north to do the arduous work of the mines. The silver was transported first to Mexico, to collect the Quinto real (a tax of 20% of the value of the silver) and then to the port city of Veracruz, from where it set sail for Europe. It is estimated that between Zacatecas and Potosí, Bolivia, 80% of the silver in the world in those centuries came from Spanish colonies.

The Spanish imposed a rigid hierarchy system on their new colonies, which would eventually comprise a vast area on the American continent. People born in the Spain itself, called peninsulares, headed everything. Just below these were the Creoles, of "pure" Spanish blood but born in America. Beneath both classes resided the indigenous people, who were generally allowed to live separately and continue to speak their own language, but they also did not have many rights or status in this new society.

One thing that the Spanish did not allow the indigenous people was to maintain their indigenous religion. The Spaniards of that time were fervent Roman Catholics, and for them it was not just an opportunity, but an obligation, to spread the Christian faith to their new subjects. There was resistance at first, but the Spanish were persistent in this area, and they were resourceful as well. For example, the Spanish used to install their churches in sites that were already sacred to the indigenous people, thus connecting them with indigenous beliefs. One day, according to legend, a poor indigenous man named Juan Diego saw the Virgin Mary, who posted her image on the ayate he wore. In time, people of indigenous descent would become some of the most faithful and fervent Catholics in New Spain. In 1782, Miguel Hidalgo (a Creole himself) would become a priest who shepherded this flock, even learning their culture and languages.

The colony grew in importance and prestige for Spain through the decades and later, the centuries. Over time, strong weaknesses could be noted in their hierarchy system, the most obvious being that many children were born to mixed parents, that is, for example, to a Creole father and an indigenous mother. Such children were called mestizos and although they were denied access to high positions of power, they were not quite as subjugated as the “pure” indigenous people. It is easy to imagine that through the generations, these mestizos made up more and more of the population of New Spain.

Another flaw in the system is that after the beginning, of course, there were much more Creoles in New Spain than Peninsulares, but the latter still possessed more authority. This division grew over the years, eventually causing many grudges between these two powerful groups.

Each decade, a smaller proportion of peninsulares reigned over a larger population of Creoles, Natives, and, above all, Mestizos. As New Spain approached its fourth century of existence, the system was becoming very unstable. The slightest nudge might cause it to come tumbling down. Miguel Hidalgo would provide that nudge.

Mark Plum is an Index contributing writer who will be producing stories on Latino culture in the West Liberty area for many weeks.

Plum, a teacher in the West Liberty Schools, said he is open to almost any ideas for stories and can be contacted by calling him at 219-471-0748 or by e-mail at mplum@wk.k12.ia.us, or by writing to the Index office at indexnews@Lcom.net

The series is associated with a special grant the newspaper won from the Iowa Newspaper Foundation.

Comments