Early tourism in Iowa and West Liberty

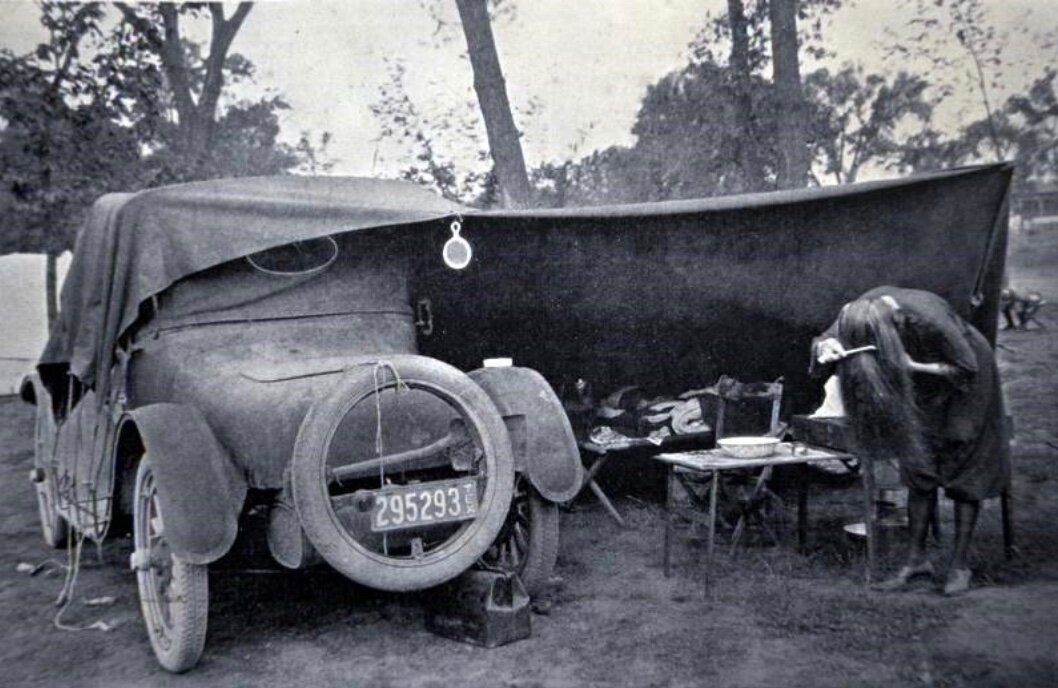

At the beginning of the 20th century, auto touring and camping in this country was in its infancy. The best of the outfits were no more than an old model of a car, a tent, a few cooking utensils and some blankets.

Many had for shelter only a strip of canvas stretched between the car and a couple of stakes set in the ground. Some merely cut the supports of the car’s front seats and tilted them backwards to form a bed. A box, bolted onto the running board of the car would hold their supplies.

There were no public campgrounds or parks maintained for campers at this time. Instead, they’d secure permission (or not) on a private property or farm, or a school or church, and park along the roadside. Anywhere there was water available and room to park seemed to fit the bill.

Over time, farmers became less hospitable to the campers, who’d unfurl their tents and make themselves right at home. This was getting to be such a common practice that farmers were becoming less welcoming.

The roads then were as crude as the equipment. Very few were paved, and most were full of ruts. Some tourists traveled in groups for safety and sociability purposes, and to help each other through the sand and mud.

A New Era

The manufacture and accessibility of improved automobiles created a need to travel, and automobile highways gave people a place to go. Americans were no longer held back by distance, and they yearned to see what lay beyond the limits of their hometowns.

With most middle class families able to afford a car, by 1915 Iowa ranked first in the nation in cars per capita, with 147,000 vehicles.

Auto camping soon became the rage, as people learned what it felt like to get in their cars and drive. Towns and cities were urged to do everything they could to be hospitable and welcoming to this new era of travelers.

Municipalities near highways began opening up their public parks and similar areas to the campers. The parks would offer amenities such as lights and water, shade, firewood, tables and benches and often showers/baths and a rest house.

This increased car travel also led to the formation of many new businesses, as the campers would often drive downtown in the city they were staying to shop, eat, and for entertainment.

It was estimated there were 3000-6000 tourist camps across the country, at the height of auto camping popularity.

Guidebooks were distributed extolling the virtues of the towns along the route, and free camp manuals were passed out to tourists on request, or were available from the U.S. Touring Information Bureau in Waterloo.

Listing info in the guidebooks would usually state the capacity of the park (which generally ranged from 50-500 cars at Iowa sites), the amenities provided, directions, and a list of the local stores and restaurants.

Before too long, the free auto camps began competing to try and outdo the amenities offered by neighboring parks. Some started charging a small fee.

Family auto camping trips were a very popular pastime in the USA in the 1920s. Some travelers even built tent trailers, which were constructed basically of a wooden platform for the folding canvas tent, mounted on a wheeled, single axle; within a few years there were companies manufacturing recreational trailers. Many people used travel trailers for ‘permanent’ inexpensive accommodations during the Great Depression, and campgrounds accepting these tenants were soon after called ‘trailer parks’.

In this area of the state, there were known tourist camps in Fairfield and Mt. Pleasant, in addition to West Liberty. Others were in Mason City, Osceola, Iowa Falls and more.

West Liberty Tourist Camp

In the early 1920s a volunteer group in town, the Community Club, began organizing a Tourist Camp, to be held at the Fairgrounds. A 1922 Index ad read: ‘Bring Your Picnic Baskets and Eat In the Shade at the Tourist Camp’.

The club had their camp info listed with the Information Bureau, and in 1923 the club’s members installed Tourist Camp signs at vantage points on roads approachable to West Liberty, and also within the city itself, to help guide tourists to the camping grounds at the Fairgrounds. The signs were in the shape of an arrow, with white letters and a blue background.

Quoting a 1924 Index article, “Only a few years ago the expression ‘Tourist Camp in Iowa’ was unknown, but today every community of any size and especially those located on the primary roads boost of a Tourist Camp. These communities maintain these camps for the purpose of drawing a trade of the people touring in automobiles and it seems that it is a type of advertising which is on a competitive basis.”

In February,1924, H.B. Melick of the Community Club was in charge of the Tourist Camp for the season. He reported a register was being made up in which all visitors would be expected to sign in. Melick also reported that a new stove would be placed at the Fairgrounds, and he promised “everything would be in readiness when the season opened.”

Unfortunately, in July of that year the Tourist Camp was the scene of a horrible murder which made headlines not only locally, but nationally as well. It left the community in shock. Two tourists, Orton Ferguson and Gabe Simmons, became involved in an argument, which ended in violence and murder. A piece of gas pipe was identified as the murder weapon. The townspeople suffered much uneasiness in the weeks that

followed, until Simmons was finally apprehended in Ohio on August 1. Two trials followed, with Simmons changing his plea several times, but in the end he was found guilty, and the jury agreed he should pay with his life. He was sent to the Ft. Madison Penitentiary and was hung on November 16, 1925. (As was the law then, a year must elapse between sentencing and punishment.)

Nevertheless, the Tourist Camp continued to be popular and finished out the season.

By April of 1925 the Tourist Camp was open for the year again. Walter Fogg, chairman of the Community Club committee overseeing the camp, announced that the Fairgrounds had been leased and would again offer free accommodations. The club leased the entire west side of the grounds from the Fair Association, and in turn sublet a portion of it for pasture, retaining the usual ground comprising the grove.

In connection with the grounds, Fogg said picnic parties were welcome, with the provision that the tables and benches not be monopolized to the inconvenience of the visiting campers.

Fogg said the camp would be conducted along the same lines as before, with stove, fuel, light, and water provided for the visitors.

West Liberty businessman J.M. Addleman reported in 1926 that an early morning walk through the Tourist Camp at the fairgrounds netted him five Fords, a Buick and a Studebaker, among others vehicles.

A March 1927 Index headline indicated the Tourist Camp at the Fairgrounds is “in readiness for the early Comets”.

It was proposed that the grounds have daily inspections and special police supervision, to make it one of the up-to-date camps on Highway 32 (predecessor of present day Highway 6).

Also in March of 1927 Will Warren, the chair of the Community Club Tourist Camp Committee that year, said things would again be done along the same lines as in the past. Will Crain would be in charge of looking after the camp and keeping tabs on the visitors, and would see that conditions on the grounds were as convenient as possible for the many visitors.

In October of that same year Crain turned in his register, wherein campers had jotted down their names and places of residence. Not all the campers complied, however, but about 700 did, proving the local grounds were popular.

Cars from everywhere in the United States and Canada spent a night or more at the grounds, it was reported. The register was filled to its covers, but the patronage at the grounds continued. By year’s end the Tourist Camp had over a thousand vehicles.

By now, trailers were allowed in the fairgrounds, for a fee of one dollar weekly.

In May,1928 the State Department of Health made a statement recommending all tourists take extra precautions when leaving home to get immunized again, as ‘vacation typhoid’ cases were on the rise. The Department went on to say that while the food and water in most of our homes is regularly inspected and examined, that is not necessarily the case in many tourist camps.

In February of 1929 Will Warren’s report of the Tourist Camp indicated a lesser number of cars for 1928, when but 235 were registered, compared with more than 1000 in 1927. This was probably partially attributed to Route 32 being blocked by paving contracts, he said.

As much the same would be the case in 1929, it was Warren’s recommendation that no attempt be made to open the area that year.

The Great Depression

The Great Depression began in 1929, and the beloved auto camps of the 1920s began to slowly disappear. Leisure travel largely turned into traveling to find work in the 1930s.

Tourist Camps left their mark, however: They changed the way Americans thought about traveling the open road and exploring their country.

The loss of the tourist camps made way for privately-owned campgrounds, cabins, and ‘motor’ hotels (motels).

More restaurants, lunchstands and filling stations began appearing.

North Point Cabins

The late Elmer Merridith, West Liberty Historian, wrote in his Rowing Down the Wapsie column about this new way of traveling, called tourism:

“Tourists were beginning to travel the highways, and as a result they needed a place to stay at night. Realizing the potential of the new business, Clare Brooke and Jesse Swart constructed tourist cabins at North Point.”

“Andy Guthrie and Findley Brooke ran the oil station and attended to the tourist cabins for a while. A really good combination because the tourists who stopped for the night usually filled up with gasoline the next morning before resuming their journey.”

Later, Mrs. Wygle helped man a restaurant and the cabins, and eventually Neil and Clare Wicks moved their Maid-Rite hamburger stand and restaurant to this spot, Elmer wrote.

McIntosh and Scott

Elmer goes on to write about Fedale McIntosh building an oil station, garage and grease rack, restaurant, and eventually several overnight cabins for tourists, on his property, also located on current day Highway 6 north of town. It was named Twin Gables. Over the oil station were sleeping rooms and bathing and toilet facilities for truck drivers.

George Scott had a variety of businesses further south, on North Columbus at Maxson. Scott had a restaurant which was open 24 hours a day at one time. He had an oil station, garage and grease rack, Elmer said. The Scotts lived in a very large house nearby and rented out spare bedrooms to tourists. He later built two tourist cabins to the rear of the restaurant, and erected yet another building which housed shower and toilet facilities, Elmer said. Scott also owned the nearby skating rink for a time.

Coincidentally, Elmer wrote, John Rohner worked at Scott’s oil station at one time as an attendant. He had a lathe in the rear of the garage portion. When not waiting on gas and oil customers, John ‘did his thing’ turning out machine parts for his customers. That was the mere beginning of what later developed into the Rohner Machine Works, Elmer said.

Building Boom

The Index reported a building boom in West Liberty in April of 1932. Glen Campbell at his North Point service station and camp was erecting a lunchstand and an additional cabin. In total there would be ten cabins, and by the 1940s all featured ‘an inner spring mattress, plenty of hot water, private shower and toilet’.

George Scott was progressing in the building of his service station, lunchstand and tourist camp near N. Columbus and Maxson Avenue.

Additionally, Hal Thompson was building a lunchstand on the lawn in front of his home on N. Columbus Street, and Louie Nichols was enlarging his refreshment stand which stood opposite the Strand on Third Street.

First Motel

By the early 1950s, the West Liberty Motel opened at 1105 N. Columbus.

Tourism seemed to thrive in West Liberty until the 1960s when Interstate 80 opened north of town. Tourist cabins were torn down, some restaurants closed, and years later, the motel ceased operating as such.

One of the original North Point cabins was moved to the West Liberty Heritage Foundation grounds, and is open to the public during visitor hours.

Comments